FEBRUARY 19, 1942: INTERNMENT

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the United States entered another global war. It transformed the country. Eight million Americans relocated. Men enlisted in the military. Other men and many women moved to work in war industries. Thousands of young women went to Washington for government jobs, becoming “G-girls.” Most Black women were already working but suddenly had better paying options. The dislocation caused by the war challenged traditional gender roles and racial stereotypes.

Not every migration was voluntary. After December 7, 1941, Hawaii put constraints on Japanese residents, but did not relocate them because they were half the population and indispensable to the economy. On the mainland, Japanese Americans were only 1% of the population. Living primarily on the West Coast, owning small businesses or vegetable farms, many were socially isolated and subjected to discrimination long before the war. Fear of more attacks fueled hate and hysteria.

The day after Pearl Harbor, Japanese war planes were supposedly sighted over San Francisco while suspected enemy submarines patrolled the coast. Lt. General John DeWitt oversaw the Western Defense Command, headquartered at the Presidio. The descendant of military leaders since the Revolution, he had dropped out of Princeton to fight in the Spanish-American War, serving in the Philippines, where the US first employed concentration camps. DeWitt had made the Army his career, retiring with four stars in 1946.

A week after Pearl Harbor, DeWitt recommended "that action be initiated at the earliest practicable date to collect all alien subjects fourteen years of age and over, of enemy nations and remove them to the Zone of the Interior." At his recommendation, blackouts were enforced and the 1942 Rose Bowl tournament was moved to Duke University in North Carolina, the only time it was not played in Pasadena.

A presidential commission chaired by Supreme Court Justice Owen Roberts conducted the first inquiry into the attack on Hawaii. Reporting to Congress in January 1942, it focused on “dereliction of duty” among military commanders. The report found some espionage by “Japanese consular agents.” There was no evidence of Japanese American involvement, but the media and California’s Democratic Governor Culbert Olson used the report to inflame public opinion.

Discrimination against Asians began in 1849 when “Chinamen” came to mine the gold fields. Chinese expertise in explosives contributed to construction of the transcontinental railroad, but cultural bias and economic competition led to exclusionary immigration laws. When Japanese immigrants replaced Chinese, the US made a Gentleman’s Agreement in 1907. Japan promised to block further migration and the US promised not to restrict the rights of migrants already here. Yet California law prohibited “aliens” from owning land so Japanese residents either lost property or put it in the names of their American-born children, who were citizens.

Strategic concerns and public prejudice prompted President Franklin Roosevelt to sign Executive Order 9066 on February 19, 1942. It authorized the Secretary of War to designate areas from which “any or all persons may be excluded.” The military would remove those persons, providing transportation, food, water and shelter.

Four days later, a Japanese submarine shelled the Ellwood Oil Field near Santa Barbara. In panic, 1400 rounds of anti-aircraft ammunition were fired at a weather balloon over Los Angeles. Within a week, DeWitt executed FDR’s order. He divided the country into military zones, from which he excluded “any Japanese, German or Italian alien, or any person of Japanese ancestry.” Given one week’s notice, about 125,000 men, women and children of Japanese descent were forced to abandon their homes and belongings.

Two-thirds of the Japanese detainees were American citizens. The others were older immigrants who had been barred from citizenship by the 1882, 1917 and 1924 immigration acts. The order also put suspect Germans into camps, primarily in the South. Restrictions on Italians, who were required to register weekly as enemy aliens at police stations, were removed on Columbus Day, 1942, just before the midterm elections. Curfews were established.

The Japanese were transported to twenty-six hastily constructed compounds located in less populated areas of the country like Arizona and Arkansas. Eight were in the desert. Former Senator Alan Simpson (R-WY) and Representative Norman Mineta (D-CA) first met as Boy Scouts on opposite sides of a barbed wire fence in Cody, Wyoming. Conditions were humiliating, eroding cultural norms about hygiene and courtship. The disruption of family structure and gender roles gave women more autonomy. Daughters resisted arranged marriages.

In 1943 the War Department authorized formation of Japanese American combat units. The Navy and Air Force refused to accept them, but the Army inducted 20,000 men into segregated units in Europe. The 442d Regimental Combat Team was proportionally the most decorated unit in US military history. Women served in the Women’s Army Corps (WACs) and as Cadet Corps nurses.

Another part of EO 9066 dismissed all Japanese American state employees, including Mitsuye Endo, a secretary with the Motor Vehicles Department in Sacramento. She was forced to move with her parents to the Tule Lake Relocation Center, near the Oregon border. An attorney hired by sixty-three fired employees chose Endo as the ideal plaintiff. A Methodist, she had never visited Japan and her brother was serving in the military. To make the case disappear, the government offered to release her. She refused and was confined for months. In April 1944, in Ex Parte Endo, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled in her favor. “The government cannot detain a citizen without charge when the government itself concedes she is loyal to the United States.”

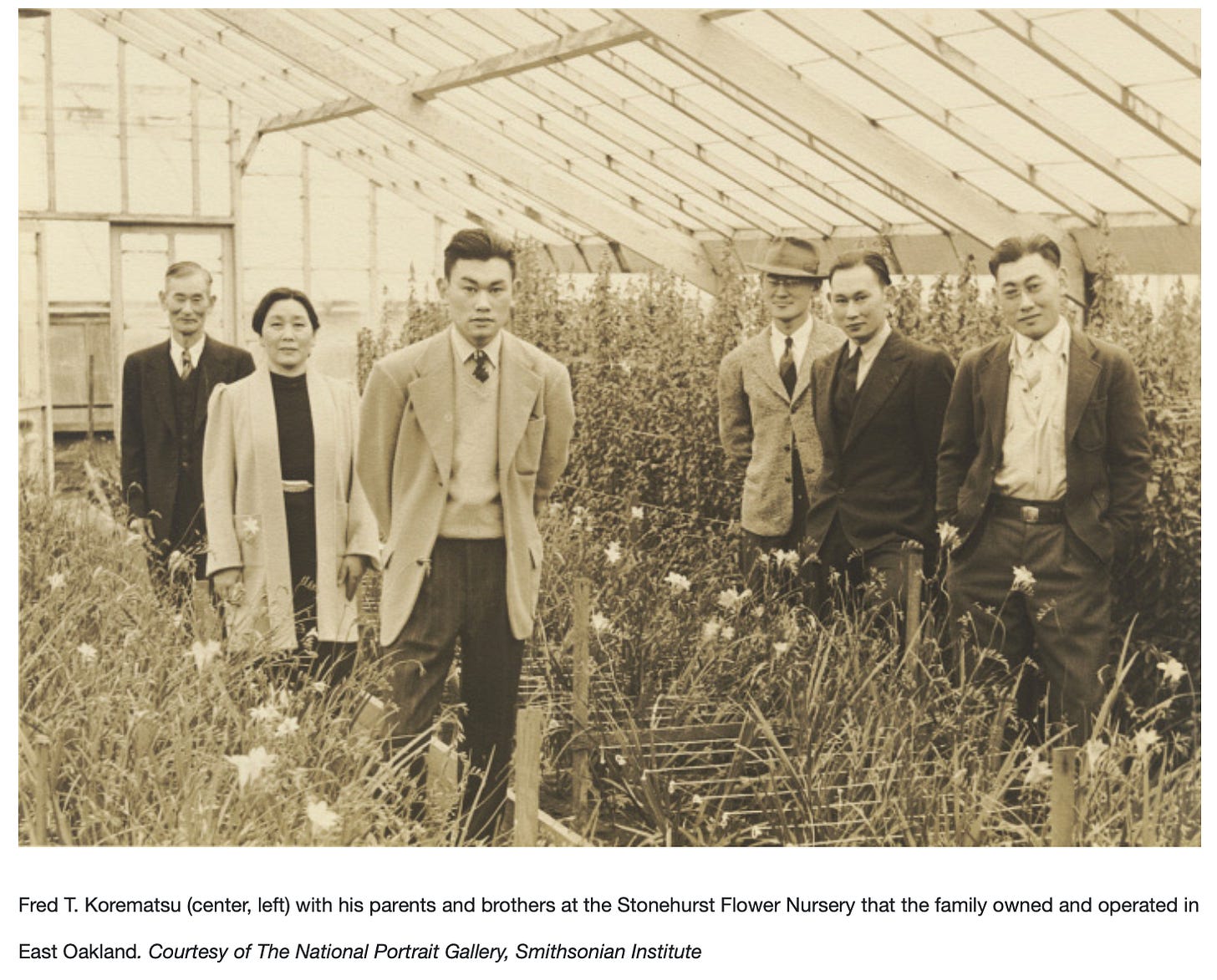

Two other internment cases reached the Supreme Court. Gordon Hirabayashi, a student at the University of Washington, was convicted of violating curfew and a relocation order. Fred Korematsu, whose family owned a flower nursery on Oakland, forged false papers to avoid internment because he was in love with a white woman. Although the Supreme Court acknowledged “a melancholy resemblance to the treatment . . . of the Jewish race in Germany,” it upheld the curfew in Hirabayashi v. United States (1943) and the legality of internment in Fred Korematsu v. United States (1944). In its 6-3 decision, the Court held that compulsory exclusion, while constitutionally suspect, was justified in times of “emergency and peril.”

The last camp closed in 1946. The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1943, when China was our ally. After partition, natives of India became eligible for citizenship in 1946. All Japanese immigrants could become citizens after 1952. President Ford officially repealed EO 9066 in 1976, because it contradicted “fundamental American principles. . . . We know now what we should have known then . . . We have learned from [that] tragedy . . . to treasure liberty and justice for each individual American.”

The Supreme Court’s decisions were not reversed. In 1980, a researcher who had been interned as a child, found unredacted case records in the National Archives. The “willful historical inaccuracies and intentional falsehoods” had been used to justify the Court’s defense of internment. Hirabayashi’s conviction was overturned in 1987. He had earned a doctorate in sociology, taught overseas and moved to Canada. Korematsu had worked as a draftsman. When his conviction was vacated in 1983, he responded: “If anyone should do any pardoning, I should be the one pardoning the government for what they did to Japanese American people.”

In 1988, President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act. Admitting “race prejudice, war hysteria and a failure of political leadership,” it apologized to Japanese detainees and provided reparations of $20,000 for each survivor. In 1998, President Clinton gave Fred Korematsu the Presidential Medal of Freedom. President Obama presented it posthumously to the Hirabayashi family.

Endnotes:

· Republican Earl Warren succeeded Culbert Olson as Governor in California (1943-1953), when President Eisenhower appointed him Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Warren later wrote that he pressed the Court to desegregate public education in the Brown decision because he had not done enough to end Japanese internment.

· In May 2011, to mark Asian American and Pacific Islander Heritage Month, Acting Solicitor General Neal Katyal spoke in the Great Hall at the DOJ. He issued the first public confession of the department’s “ethics lapse” in the internment camp cases.

· Jeanne Wakatsuki Houston, whose acclaimed memoir, Farewell to Manzanar (1973) recounted her childhood in a camp, died on December 21, 2024.

Today, internment camps are back in the news.

SOURCES:

Photo credits: public domain unless noted.

“Executive Order 9066: The President Authorizes Japanese Relocation,” History Matters, www.historymatters.gmu.edu/d/5154

“John Lesesne DeWitt,” US National Park Service, https://www.nps.gov/people/john-lesesne-dewitt.htm

David M. Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (Oxford University Press, 1999).

Elaine Tyler May, Pushing the Limits: American Women 1940-1961, from Rosie the Riveter to the Baby Boom and Beyond (Oxford University Press, 1994).

https://dp.la/exhibitions/japanese-internment/hone-family/women

Michelle Konstaninovsky, “Mitsuye Endo: The Woman Who Took Down Executive Order 9066” (May 14, 2019), https://people.howstuffworks.com/mitsuye-endo-executive-order9066.htm

“Hirabayashi v. United States,” Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/320us81

“Korematsu v. United States,” Oyez, www.oyez.org/cases/1940-1955/320us214

Erick Trickey, “Fred Korematsu Fought Against Japanese Internment in the Supreme Court . . . and Lost,” Smithsonian Magazine (January 30, 2017), www.smithsonianmag.com/history/fred-korematsu-fought-against-japanese-internment-supreme-court-and-lost-180961967/

Lorraine K. Bannai, Enduring Conviction: Fred Korematsu and his Quest for Justice (University of Washington Press, 2015).

Elisabeth Griffith, FORMIDABLE: American Women and the Fight for Equality, 1920-2020 (Pegasus, 2022).