Author’s note: Recently Jeffrey Rosen, President of the National Constitution Center, hosted a conversation about the country’s founding documents, the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. Harvard professor Annette Gordon-Reed, president of the Organization of American Historians, described the Declaration as a diplomatic document, presenting the Americans’ rationale for breaking away from Great Britain. The Parliament had denied their rights as free Englishmen to representation in determining the laws that governed them, among other “usurpations” by King George III.

Akhil Reed Lamar and David Blight, professors at Yale, described the Declaration’s emphasis on equal rights for all as its crucial and consequential purpose. The three scholars elaborated on how change agents from Elizabeth Cady Stanton to Frederick Douglass to Abraham Lincoln embraced its aspirational language to expand our democracy. The words “equal,” “liberty” and “justice” appear in the first paragraphs of both the Declaration and the Constitution.

I believe that our history is the biography of an experimental, still fragile, frequently flawed democracy, aspiring to ensure equality, liberty and justice for all. Ours is a story of successes and set backs, of resistance, division, perseverance and courage.

“I love America more than any other country in the world and exactly for this reason, I insist on the right to criticize her perpetually.” James Baldwin, 1955

Abigail Adams’ husband John spent most of 1776 in Philadelphia, as a delegate to the Second Continental Congress. Fiercely patriotic, Adams (MA) argued forcefully for independence from Great Britain. The Congress appointed him to a committee of five, with Benjamin Franklin (PA), Thomas Jefferson (VA), Robert Livingston (NY), and Roger Sherman (CT), to draft a statement of their rationale.

Adams urged Jefferson to write their declaration, because the Virginian was a gifted wordsmith and “I am obnoxious, suspect, and unpopular. . . You are very much otherwise.” Attended by his enslaved servant, Robert Hemings, Jefferson completed his task at a portable desk he designed. In seventeen days, he produced a daring, radical and aspirational document. “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights . . . That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.”

The Congress deleted a quarter of his draft. On July 2, it adopted a resolution to declare independence from Great Britain. On July 4, it formally endorsed the Declaration of Independence. Irish immigrant John Dunlop printed 200 copies. A copy was sent to England; another was read to colonial troops. On August 2, the Declaration was embossed on parchment for delegates to sign. As president of the Second Continental Congress, John Hancock was the first to sign. The story about his writing in large cursive, “so the King could read it without his spectacles,” is a myth.

By signing the Declaration of Independence, fifty-six privileged, educated, white men pledged “to each other our Lives, our Fortunes and our sacred Honor” and committed treason against Great Britain.

Five were captured by the British, tortured and died. Nine died from battlefield wounds. Three lost sons in the war. Twelve had their homes ransacked and burned. Wives were imprisoned; children perished. The British Navy seized a Virginia trader’s ships. During the final battle at Yorktown, British General Cornwallis seized Thomas Nelson’s home as his headquarters. Nelson urged Washington to open fire. His home destroyed, Nelson died bankrupt.

Forty-one signers were enslavers, but all of them would have benefitted from businesses tied to a slave economy. Arthur Middleton (SC), whose plantation is now a tourist attraction and a wedding venue near Charleston, enslaved 100 people. Only one Southerner, George Walton (GA), held no human chattel.

The fictional president on the television series The West Wing (1999-2006, NBC) was named Josiah Bartlett, for one of New Hampshire’s signers. His wife’s name was Abigail.

On July 2, 1776, John Adams wrote his Abigail: “The Second Day of July 1776 will be the most memorable Epocha in the History of America. It ought to be commemorated as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized by Pomp and Parade, with Shews [sic], Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.” Irritated by celebrations on July 4, Adams never celebrated the Independence Day. Famously Adams and Jefferson died within hours of each other on July 4, 1826, the Declaration’s fiftieth anniversary.

Adams dismissed Abigail’s demand that the Congress “remember the ladies” in its deliberations. It never considered rights for women: very few had ever had a legal identity separate from their fathers or husbands. While it wrestled with how to treat enslaved African Americans, the Congress ignored Indigenous Americans, because they were members of foreign tribes. In 1776, power rested in privileged white men. Equality was not equally accessed.

Abigail Adams, undated portrait by Gilbert Stuart (public domain)

Women had responded to boycotts and blockades with creative solutions, making tea from sassafras, replacing sugar with honey, substituting “homespun” cloth for English textiles. During the war, they made bullets and bandages. Most of Washington’s ragtag Continental Army were shopkeepers or farmers. Their female relatives were left to run their operations.

While Benjamin Franklin sought European alliances and loans, his estranged, common law wife Deborah Read ran his printing business. His daughter Sarah Bache raised $7,000 to purchase cloth and organized women to make shirts for American soldiers. Mary Katherine Goddard ran her family’s printing business, publishing the Baltimore Journal from 1774-1784. Because of her reliability, Congress authorized her to print the copy of the Declaration that included the signers’ names. Appearing at the bottom, hers is the only female name on the document.

Sybil Ludington repeated Paul Revere’s ride in 1777, racing forty miles to warn militiamen of a British attack. Deborah Champion carried papers to General Washington. Stopped by a British sentry, she was dismissed as “only an old woman.” Emily Geiger was a successful spy.

Some wives followed their husbands to war, cooking, washing, mending and nursing. Some served on the front lines. Nicknamed “Molly Pitcher,” Mary Ludwig Hays McCauley, the illiterate, pregnant wife of a barber, was not taking water to thirsty soldiers. She was hauling buckets to cool cannon, so they could be re-fired more quickly.

Engraving of “Molly Pitcher” at the Battle of Monmouth, June 1778. (National Archives)

After her husband John was killed and before she was captured, Margaret Corbin was wounded by enemy fire, but kept loading small artillery. Deborah Sampson enlisted as Robert Shurtleff and fought on the front lines. When she was wounded, rather than reveal her identity, Sampson stitched her own wounds. Mercy Warren became a propagandist and historian of the Revolution. Julia Stockton Rush, 18, the daughter and wife of Declaration signers, chastised her husband Benjamin for criticizing Washington’s leadership of the Continental Army.

L: Mercy Otis Warren c. 1763, portrait by John Singleton Copley (public domain) R: Julia Stockton Rush, 1776, portrait by Charles Willson Peale (Winterthur Museum)

The 1924 Native American Citizenship Act, promoted by Indigenous women, Marie Louise Bottineau Baldwin and Zitkala-Sa (Gertrude Simmons Bonnin), granted conditional citizenship. Sixteen states with large Indigenous populations denied voting rights until they were won in post-World War II court cases and secured by the 1965 Voting Rights Act. They remain vulnerable.

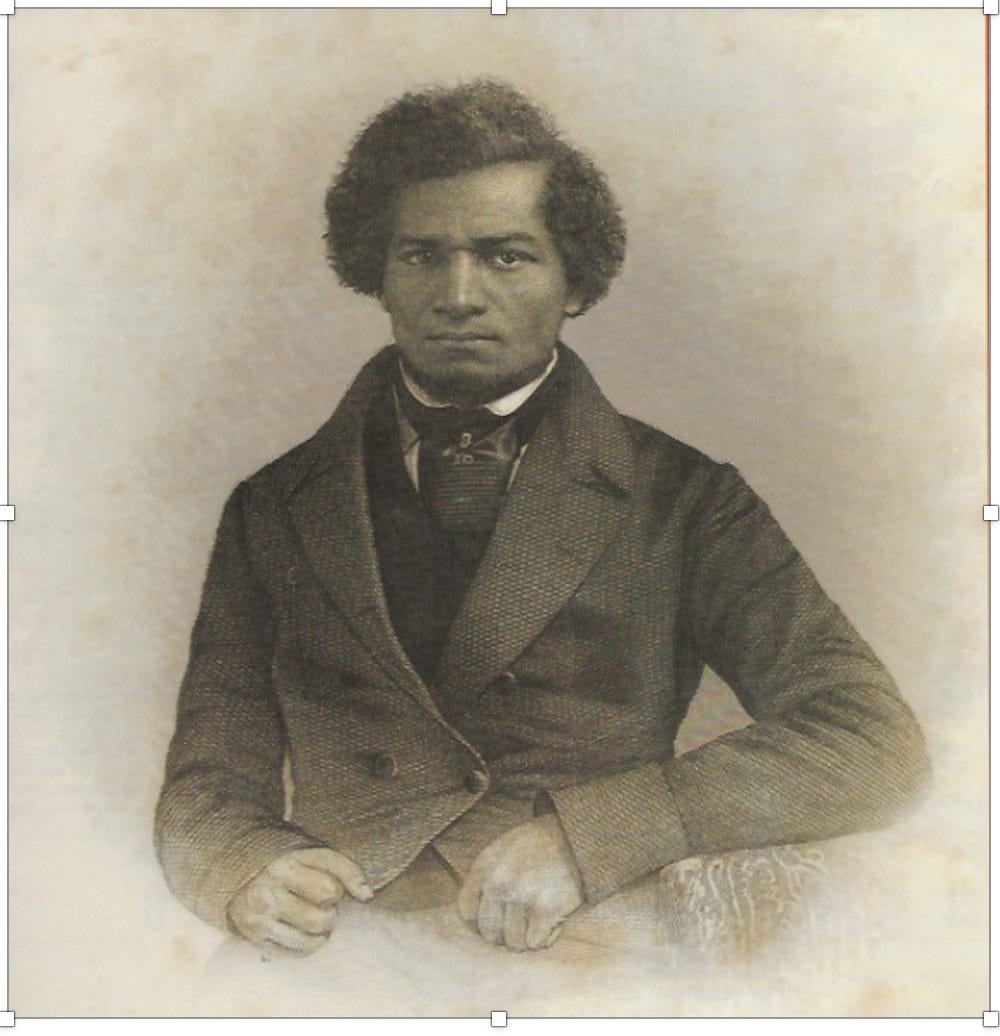

Abolitionists relied on the Declaration to make the case for emancipation. On July 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass addressed an audience of 600 at an Independence Day celebration, sponsored by the Rochester, NY, Ladies’ Anti-Slavery Association. Formerly enslaved, the editor of The North Star was the most famous Black man in America. The powerful orator asked his audience, “What to a Slave Is the Fourth of July?” Douglass commended the Declaration’s authors’ commitment to “life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.”

“Fellow citizens, I am not wanting in respect for the fathers of this republic. The signers . . . were brave men. . . . They were statesmen, patriots and heroes, and for . . . the principles the contended for, I will unite with you to honor their memory.” Then Douglass turned critical.

“Were the great principles of freedom and of natural justice . . . extended to us? . . . The blessings in which you . . . rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not me. . .

This Fourth of July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

Douglass biographer David Blight called it a “rhetorical masterpiece” and “a symphony in three movements” – praise for the founders, followed by a condemnation of the horrors of slavery, ending with the hope that the nation might yet extend freedom to the enslaved.

Frederick Douglass, 1855 (Gilder-Lehrman Institute of American History calendar)

When Lincoln was president, the only national holidays were George Washington’s birthday and the Fourth of July. In his 1863 Gettysburg Address, President Lincoln appropriated the Declaration to redefine the purpose of the Civil War. “Four score and seven years ago our fathers brought forth on this continent a new nation, conceived in liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal.” Dedicating the first national military cemetery, Lincoln resolved “that these dead shall not have died in vain, that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom, and that government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.”

In July 1848, Douglass was the only African American to attend the Seneca Falls women’s rights convention. One of its organizers, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, had drafted a Declaration of Rights and Sentiments for attendees to approve. Based closely on the Declaration of Independence, it declared “that all men and women are created equal.” It replaced the tyrant King George with “all men.” The resolution proposing voting rights for women would have failed without Douglass’ support.

Writing to Susan B. Anthony in 1858, Stanton voiced her frustration with Fourth of July celebrations. “How rebellious it makes me feel when I see Henry going about where and how he pleases . . . As I contrast his freedom with my bondage, and feel that, because of the false position of women, I have been compelled to hold all my noblest aspirations in abeyance in order to be a wife, a mother, a nurse, a cook and a household drudge. . . I have been alone today as the whole family except [baby] Hattie and myself have been out to celebrate our national birthday. What has a woman to do with patriotism?”

After the 2022 Dobbs decision, some American women wore black in solidarity and not celebrating the Fourth of July, “because it certainly is not a day of independence for us,” one woman tweeted. “It never was.”

In 1876, Anthony determined that the Declaration’s Centennial provided an opportunity to present suffragists as patriots and to propose a new Declaration of Women’s Rights. Stanton was unenthusiastic but Anthony persuaded her to write the document. The plan was to present it in Philadelphia, together with Lucretia Mott, then 83.

The Centennial was a summer-long event. An enormous steam engine powered 8,000 machines in the main exhibit. Almost everything made in the America was on display, including caskets, false teeth, safety pins and the newly invented telephone. There were fragments of the unfinished Statue of Liberty. To focus on female contributions, the Women’s Centenary Committee funded the ornate Women’s Pavilion, to display women’s artistry and with its own engine, powering machines operated by women.

When Anthony’s request to be part of the July Fourth ceremony was declined, she decided to crash the event. Neither Stanton nor Mott participated. Armed with press passes, Anthony and four other women marched into Independence Hall. The women advanced on the startled chairman, presented a parchment copy of their Declaration and filed out while distributing copies. Once outside, Anthony mounted a bandstand and read it to onlookers.

Stanton was discouraged. She refused to attend the 1878 anniversary of Seneca Falls. “As I sum up the indignities toward women, as illustrated by recent judicial decisions – denied the right to vote, denied the right to practice [before] the Supreme Court, denied jury trial – I feel the degradation of my sex more bitterly than I did . . . that July.”

That same year, Senator Aaron Sargent (R-California) introduced a constitutional amendment to enfranchise women. His wife, Ellen Clark Sargent, was an ardent suffragist. It was called the Anthony Amendment, which annoyed Stanton because Susan had not been present in 1848. Written by Anthony, its wording had not changed when it was ratified as the Nineteenth Amendment in August 1920.

The effect of women’s contributions to the Revolution and American independence was summed up by a British officer: “We may destroy all the men in America, and we shall still have all we can do to defeat the women.”

The Fourth of July is my favorite holiday. My family dresses up in patriotic colors, sings patriotic songs, take turns reading the Declaration aloud, watches fireworks (and Jaws), and puts out multiple flags. Despite today’s headlines and the Trump administration’s challenges to the rule of law, the separation of powers and equal rights for all, let’s celebrate. Ours is a great country. To despair is to surrender. America’s revolutionary ideals about equality deserve our best effort to sustain and protect our democracy. Remember Anthony’s words, urging us to “educate, organize, agitate” and vote. Unfortunately, there’s no proof she ever said, “Failure is impossible.” It’s up to us.

PS: I also feel strongly that patriotism is not partisan and that the flag belongs to all of us. Note my 14-year-old grandson’s attire at today’s Nats game. The Nationals lost to the Red Sox, 11-2, but since his other grandmother lives in Boston, he’s claiming his team won.

SOURCES:

Linda Grant DePauw and Michael McCurdy, Founding Mothers: Women in America in the Revolutionary Period (Houghton Mifflin, 1975)

Linda Grant DePauw and Conover Hunt, “Remember the Ladies:” Women in American 1750-1815” (Viking, 1976).

Petula Dvorak, “Why Many Women Took a Knee This July Fourth,” Washington Post (July 4, 2022), https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/07/04/july-fourth-abortion-women-boycott-celebrations/

Stephen Fried, “A New Founding Mother,” Smithsonian Magazine (September 2018), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/rediscovering-founding-mother-180970037/

David W. Blight, Frederick Douglass: Prophet of Freedom (Simon & Schuster, 2018).

Elisabeth Griffith, In Her Own Right: The Life of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (Oxford, 1984).

Michael D. Hattem, Past and Prologue: Politics and Memory in the American Revolution (Yale University Press, 2020).

“A Nation’s Story: “What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?” https://nmaahc.si.edu/blog/series/paradox-and-promise

Cari Shane, “Before Lady Liberty,” Smithsonian Magazine (October 2023), https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/before-lady-liberty-lady-columbia-180982722/

Emily J. Tiepe, “Will the Real Molly Pitcher Please Stand Up?” Prologue Magazine (Summer 1999), https://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/1999/summer/pitcher.html

https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/suffragists-crashed-centennial-celebration/

Thanks for this detailed report and explanation. In my family, we claim a non-signer (John Alsop/NY) who thought that America could still come to terms with Britain. I call him one of the "nervous merchants".