June 28, 1969: STONEWALL

The punch that started the riot at the Stonewall Inn and launched the Gay Pride Movement was thrown by a drag queen. On Saturday, June 28, 1969, at 1:20 a.m., eight members of the NYPD Public Morals Squad raided the Christopher Street bar in Greenwich Village. “It was our Rosa Parks moment,” recalled one man, who compared gay bars to sanctuary churches. The fight for equal rights for the LGBTQIA community was more recent, less publicized and until 1969, less violent than the civil rights movement. Both fought for their rights under the democratic principles of equal protection of the law and equality for all.

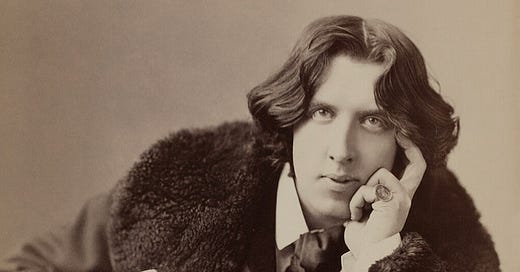

Male homosexuality was illegal, scorned and mostly ignored in western society, with exceptions for public figures like Oscar Wilde, the witty Irish poet and playwright. The married author of The Picture of Dorian Gray and The Importance of Being Ernest was a public celebrity in Iate-Victorian England, until his conviction for gross indecency with other males. In 1895, he was sentenced to two years hard labor. The charge was brought by the 9th Marquess of Queensbury, whose son was Wilde’s lover. Alfred Lord Douglass was not charged.

Oscar Wilde, 1882

The era’s scientific experts deemed normal (“virtuous”) women incapable of sexual passion (. . . pausing to let that sink in . . . ). The behavior of white whores and Black jezebels was abnormal, making them social outcasts. So no one objected to maids sleeping together in the servants’ quarters or to the “Boston marriages” of Bryn Mawr president M. Carey Thomas and railroad heiress Mary Garrett; of Mount Holyoke president Mary Emma Woolley and English professor Jeannette Marks; of feminist organizer Susan B. Anthony and her numerous “nieces;” of twice-widowed suffrage leader Carrie Chapman Catt and Mary (Molly) Garrett Hay, next to whom she was buried; or New Dealer Molly Dewson and (patron) Polly Porter. Her father invented the reaper machine and eventually formed International Harvester.

President Woolley & Professor Marks, 1923

Among so many others, as Lillian Faderman, “the mother of lesbian history,” documented in To Believe in Women: What Lesbians Have Done for America – A History (1999). The possibility of lesbian relationships was either inconceivable or ignored until historian Carroll Smith-Rosenberg presented her research in “The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations Between Women in Nineteenth-Century America,” at a Berkshire Women’s History Conference in 1974. She explored the history of lesbianism and connected it to gender construction, the mythology of sex role socialization, and how children learn what behaviors are expected of them or are appropriate to their gender at birth.

No reviewer outed the author. Her paper was published in the first issue of SIGNS: Journal of Women in Culture and Society (1975). With Gerda Lerner and Linda Kerber, Smith-Rosenberg was among the founders of the academic field of women studies in the early 1970s. Conferences and journals were created to counter the exclusion of women’s history from traditional (white male) forums. From the start, women’s/gender studies has been inclusive, because women as a vastly diverse cohort.

Until recently, biographers of homosexual subjects were reluctant to risk their reputations as Famous Authors or Founding Mothers in homophobic America. Yet many of these Greats would have failed without the emotional and financial support of unacknowledged partners.

In 2013, when President Obama alluded alliteratively to “Seneca Falls . . . Selma and . . . Stonewall” in his second inaugural address, he acknowledged advances for women, Black Americans and homosexuals, but abbreviated the long, hard history of those movements. None of them originated at those locations.

The gay rights movement began in the US and Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. In 1924, Henry Gerber founded the Human Rights Society in Chicago, the first and oldest documented gay rights organization in the US. World War II offered unanticipated opportunities for young men and women of any orientation, as they joined the sex-segregated armed services or moved to big cities for jobs in government or war production industries, finding privacy and partners.

After the war, the Mattachine (a group of masked players) Society, a gay rights organization founded by Harry Hay in Los Angeles in 1950, aimed “to eliminate discrimination, derision, prejudice and bigotry.” In 1955, the Daughters of Bilitis (a fictional contemporary of Sappho) was organized in San Francisco, to provide a social network and support for women who were afraid to come out. Lorraine Hansberry, whose 1959 play, A Raisin in the Sun, was the first written by a Black woman to open on Broadway, was a member of the Daughters.

Zoologist Alfred Kinsey’s 1948 and 1953 reports, about the sexual behavior of men and women, shocked the country by portraying both sexes as sexually active and actively interested. Among his 12,000 white, middle-class subjects, 37% of men had had at least one homosexual experience, compared to 6% of women. Kinsey found that “persons with homosexual history are to be found in every age group . . . social level . . . [and] conceivable occupation, in cities and on farms, and in the most remote areas of the country.” The conclusion that 10% of Americans are homosexuals is based on his research.

Many religious and social institutions condemned homosexuality as a moral failure. They feared it undermined the country as it confronted the Soviet Union and Red China. A 1950 Senate report, “Employment of Homosexuals and Other Sex Perverts,” concluded that homosexuals were security risks because they “lack the emotional stability of normal persons.”

Senator Joe McCarthy’s post-war hunt for communists became a “lavender purge” of homosexuals, a sexual orientation some of his biographers would suspect the Catholic Republican from Wisconsin shared. In 1953, President Eisenhower issued Executive Order 10450, which allowed federal employees to be fired for “sexual perversion.” More than 5,000 men and women resigned rather than be exposed as “moral misfits.”

Franklin Kameny, an astronomer with a Harvard doctorate working for the Federal Map Service, fought his 1957 dismissal, until the Supreme Court finally denied his appeal. Kameny organized the gay rights movement in Washington, DC, picketing the White House with signs demanding “CITIZENSHIP FOR HOMOSEXUALS.” His greatest contribution was his pivotal role in persuading the American Psychiatric Association to remove homosexuality from its list of mental disorders.

In 1973, the APA board declared that homosexuality “by itself does not necessarily constitute a psychiatric disorder.” Conservative members demanded a referendum. The board’s decision was affirmed, 5,854 to 3,810. Based on that previous supposed pathology, homosexuality was illegal in every state except Illinois, which had decriminalized sodomy in 1961. When President Obama signed a 2009 order granting benefits to same-sex partners of federal employed employees, he gave the first pen to Dr. Kameny.

Gays were regularly bullied by police and barred from jobs, housing, dancing together and wearing clothes that were not gender specific. At the time, less attention was paid to lesbians and trans women, who were banned from men-only gay bars, as straight women were from most bars. Protesting violent police harassment, lesbians, drag queens and trans people started the Compton Cafeteria Riot in San Francisco in 1966, predating Stonewall.

In 1969, patrons of the Stonewall Inn were being herded into the street and pushed into paddy wagons when Storme DeLarverie, a mixed-race singer and drag performer, punched an arresting officer. As the cop swung his bully club, they gay men attacked. They threw bricks, bottles and punches; the police barricaded themselves inside the bar. The clash lasted until reinforcements arrived but rioting continued for four days.

Media coverage of the confrontation triggered an explosion of activism, leading to the Gay Liberation Front, an allusion to the War in Vietnam. The Christopher Street Liberation Day March on the first anniversary of Stonewall morphed into annual gay pride parades across the country. In the first Pride Parade, around 4,000 people marched fifty-one blocks from Greenwich Village to Central Park.

The term “pride” was coined by activist Craig Schoonmaker in 1970. “There’s very little chance for people . . . to have power,” he explained decades later, “but anyone can have pride in themselves.” Celebrating pride countered a culture in which queer people were shamed for being who they were.

Scholars of Stonewall debate the connection between the riot and grief among gays following the death of Judy Garland. Her New York City funeral, attended by 20,000 people, was June 27, the day before the Stonewall raid. A “disproportionate part of her nightly claque,” wrote Time magazine in 1967, “seems to be . . . the boys in tight pants.” To be a “friend of Dorothy,” referring to Garland’s role in The Wizard of Oz, was code for gay because Dorothy befriends the Cowardly Lion, who calls himself a sissy. When gay bar patrons were required to sign in, Dorothy Gale and Judy Garland were popular pseudonyms.

Garland fans believe her song, “Over the Rainbow,” inspired the rainbow flag. Others credit Harvey Milk, the California activist. In 1978 he commissioned artist and drag queen Gilbert Baker to create a symbol for an upcoming parade. He wanted something joyful and inclusive, to counter memories of the pink triangles Nazis used to designate queer people. After Milk’s murder, the demand for LGBTQ flags grew. The pink and turquoise stripes were removed. In 2017, Philadelphia’s Office of Diversity and Amber Hill added stripes to represent the Black and brown communities.

Later in 1969, in Norton v. Macy, the US Court of Appeals for DC declared homosexual civil servants could not be fired unless their behavior harmed “the efficiency of the service.” In 1975, the Pentagon issued its first security clearance to a known homosexual. In 1974, Kathy Kozachenko was the first openly gay American elected to public office, when she won a seat on the Ann Arbor, Michigan, city council. In 2024, Delaware elected Sarah McBride (D) to be the first trans woman to the US House of Representatives.

Representative Sarah McBride (D-DE)

In 1977, Harvey Milk won a seat on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, which was chaired by Dianne Feinstein. He introduced an ordinance, protecting gay employment rights. It passed 11-1. The one anti-vote was cast by supervisor Dan White. Milk had promised to support White’s bill for a mental health facility. Milk changed his mind and the bill lost by one vote. White vowed to vote against anything Milk porposed. After Milk’s bill passed, White resigned. The next day, November 27, 1978, the former police officer and decorated firefighter avoided security, entered City Hall through a basement window and murdered both Mayor George Moscone and Supervisor Milk, shooting them multiple times.

Born in New York in 1930, Milk had had an erratic career. He enlisted in the US Navy during the Korean War and served on a submarine rescue ship, as a diver and a dive instructor. In 1955, the Lieutenant J.G. (junior grade) was forced to accept an “other than honorable” discharge to avoid being court-martialed for homosexuality. In 2021, President Biden named a Navy replenishment oiler, which supports carrier strike groups, the USNS Harvey Milk.

Yesterday, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth announced that the USNS Harvey Milk will be renamed for a World War II sailor, Chief Petty Officer Oscar Peterson, who received a posthumous Medal of Honor for heroic action during the Battle of the Coral Sea. In a video posted on social media, the Secretary declared that he was “taking the politics out of ship naming.”

In June 2016, the National Park Service made the Stonewall Inn is the only NPS site devoted to LBGTQ history. President Trump’s Executive Order 14168, “Defending Women from Gender Ideology Extremism and Restoring Biological Truth to the Federal Government,” recognizes only two genders. The NPS website now describes Stonewall as an “LGB” milestone. It removed any references to transgender. The word “transgender” was not in use in 1969. Trans activists like Marsha Johnson and Sylvia Rivera used female pronouns and described themselves as gay, queens, drag queens and transvestites.

At least Stonewall still has a web presence. When I searched for “history of homosexuality in the US,” this page appeared:

Fifty years after Stonewall, in 2019, New York’s police commissioner apologized for the raid. From 1996 to 2020, gay cops in uniform marched in pride parades. After George Floyd’s death, they felt less welcome. Individual police departments set rules, like not wearing uniforms to a political event. This month, Washington, DC ‘s mayor Muriel Bowser and Chief of Police Pamela Smith marched in the World Pride Parade here. Smith and her officers were in uniform.

Author’s note: Ten years ago, on June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court declared same-sex marriages legal in every state, deciding 5-4 in Obergefell v. Hodges. My plan had been to conclude this PINK with that decision. But I learned to much about LBGTQ rights in America, for the backstory, that Obergefell will have to wait. One wonders what its status will be next year?

If you are a free subscriber, please consider a paid subscription, to support fact-based history about our diverse, aspirational democracy. These essays are my attempt to preserve and fortify our country’s foundational values, the rule of law and equal rights for all.

SOURCES

Photo credits: public domain unless noted.

Stonewall Uprising, directed by Kate Davis ad David Heilbroner, broadcast April 24, 2011, https://pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/films/stonewall

Joanne Meyerwitz, “Stonewall: 50 Years Later,” The American Historian (May 2019).

Martin B. Duberman, Stonewall: The Definitive Story of the LGBTQ Rights Uprising That Changed America, rev. ed. (Penguin Random House, 2019).

David Carter, Stonewall: The Riots that Sparked the Gay Revolution (St. Martins Griffin, 2010).

History.com editors, “Pride Month 2025” (May 28, 2025), https://www.history.com/articles/pride-month.

“History of Pride Month: Joint Base Andrews,” https://www.jba.af.mil/News/Article-Display/Article/2669499/the-history-of-pride-month/.

Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz, The Power and Passion of M. Carey Thomas (Knopf, 1994).

Anna Mary Wells, Miss Marks and Miss Woolley: The Portrait of a Lifelong Relationship Between Two Prominent and Independent Women (Houghton Mifflin, 1978).

Jacqueline Van Voris, Carrie Chapman Catt: A Public Life (Feminist Press, 1987).

Susan Ware, Partner and I: Molly Dewson, Feminism and New Deal Politics (Yale University Press, 1987).

Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, "The Female World of Love and Ritual: Relations between Women in Nineteenth-Century America," Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society (1975).

Carroll Smith-Rosenberg, Disorderly Conduct: Visions of Gender in Victorian America (Knopf, 1985).

William H. Chafe, Paradox of Change: American Women in the 20th Century (Oxford University Press, 1991).

Lillian Faderman, The Gay Revolution: The Story of the Struggle (Simon & Schuster, 2016).

Arantza Pena Popo, “A Brief History of Pride Flags,” Washington Post (June 27, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/lifestyle/2023/06/25/pride-flags-comic-history/.

“Pentagon Strips Harvey Milk’s Name from Ship,” https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/pentagon-strips-harvey-milks-name-from-ship.

Olivia McCormack, “Park Service Deletes Trans References on Stonewall Inn Monument Page,” Washington Post (February 13, 2025), https://www.washingtonpost.com/travel/2025/02/13/stonewall-transgender-lgb-national-park-service/.

Lou Chibbaro, “D.C. Police Chief and Officers Marched in Pride Parade in Uniform,” Washington Blade (June 13 ,2024), https://www.washingtonblade.com/2024/06/13/pamala-smith-mpd-march-pride-parade/.

David W. Dunlap, “Franklin Kameny, Gay Rights Pioneer, Dies at 86,” New York Times (October 12, 2011), https://www.nytimes.com/2011/10/13/us/franklin-kameny-gay-rights-pioneer-dies-at-86.html.

Elisabeth Griffith, FORMIDABLE: American Women and the Fight for Equality, 1920-2020 (Pegasus, 2022).