Today is National Rosie the Riveter Day Remembrance Day. It celebrates the American women who worked in war industries and other jobs during World War II, replacing men who were fighting at the front. Few of those women are still alive. Most of their names have been forgotten, but Rosie lives on as a cultural icon and a feminist symbol. Her image, based on a wartime poster, is everywhere, on t-shirts, mugs and magnets.

Having discouraged and sometimes legally forbidden women from working during the Depression, the government reversed its position after Pearl Harbor. To recruit women workers, its Manpower Commission circulated a jaunty jingle about a fictional riveter named Rosie, written by John Jacob Loeb and Redd Evans. “That little frail can do, more than a male can do, Rosie (rrrrrr) the riveter. Rosie’s got a boyfriend, Charlie; Charlie’s a marine, Rosie is protecting Charlie, working overtime on the riveting machine.”

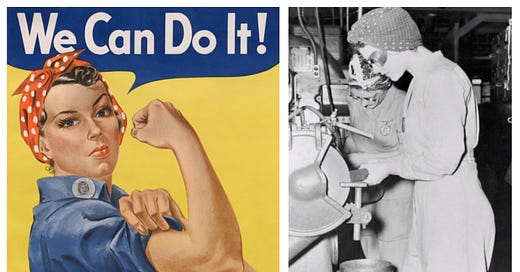

The iconic “We Can Do It” poster was designed by J. Howard Miller for Westinghouse Electric Corporation. Posted in its factories for two weeks in 1943, it was intended to deter women from skipping work or striking. It may have been inspired by a Canadian poster featuring “Ronnie, the Bren Gun Girl.” The Bren was a light machine gun, the most common weapon used by British and Commonwealth infantry forces for fifty years. Wearing a blue shirt and a red polka dot bandana, Miller’s Rosie flexed her bicep. That poster did not gain national exposure until the 1980s.

Rosie’s image as based on a news photograph taken of a woman working on a turret.

Geraldine Hoff Doyle, who had worked as a shipbuilder in Michigan, claimed to be Miller’s model. But at a 2009 Rosie reunion, Naomi Parker Fraley saw a photograph of herself, misidentified as Doyle. Fraley, who had worked at the Naval Air Station in Alameda, California, contacted the WWII Home Front National Historic Park with a newspaper clipping she had saved. It named her in the caption. It took six years and a scholarly article to correct the record.

Westinghouse poster and Naomi Parker Fraley

Nineteen-year-old Vermont telephone operator, Mary Doyle Keefe, was Norman Rockwell’s model for his May 1943 Saturday Evening Post cover. His Rosie was a strapping redhead in coveralls with her lunchbox and a riveting gun in her lap and something lacey in her pocket. She’s eating a sandwich and stepping on a copy of Mein Kampf. The pose mirrors Michelangelo’s image of the prophet Isaiah in the Sistine Chapel. Rockwell depicted Rosie as beefier than Keefe and later apologized. The US Treasury used his Rosie in war bond drives. Rockwell’s Rosie represented the changing role of women in the war, an image of “female masculinity,” accessorizing work boots and safety helmets with lipstick.

While 350,000 women served in the military, roughly six million women went to work during WWII. Sixteen-year-old Marian Sousa moved to California to care for her sister’s children when Phyllis Gould worked as a welder at Bay area shipyard. After a six-week course in engineering drawing at the University of California Berkeley, Sousa took a maritime drafting job. A week after graduating from high school in 1942, Gloria McCormack got a job at an Ohio defense plant manufacturing machine guns. Norma Jeane Doughterty, the eighteen-year-old wife of a merchant seaman, worked at the Radioplane Munitions Factory in Burbank, California, before she became Marilyn Monroe.

There were news photographs but no posters of Black Rosies. Velma Long, with a bachelor’s degree in science, worked as a clerk typist for the Navy Department in Washington, DC, the only Black woman in her office. Most war industry jobs were segregated, with African American women getting the toughest tasks at the lowest wages. Despite the upward mobility experienced by many Black women during the war, who left domestic service or jobs as field hands to work in factories, their relative position within the economy remained the same.

Factory work was hard, hot and dirty, but the war offered jobs never before available to women. White women who had worked in department stores and restaurants for $24.50/week could make $40.35/week making bombers, ships, tanks and jeeps. One Rosie recalled, “I was paid more than my husband and . . . spending it on lingerie.” The pre-war auto industry had been 90% male. When plants were retooled for war production, 25% of the workforce was female. Half of women factory workers were in non-defense industries, filling places in machine shops, oil refineries, lumber and steel mills.

Women working in these occupations with men questioned the concept of “male jobs” and pay differentials. To pay women the same wage to do the same job as a man challenged ingrained attitudes about sex roles, but to pay women less undercut the value of the task when men did it. The government supported equal pay on account of “justice,” but mostly to sustain male wage rates and increase purchasing power. To protect the value of jobs for returning veterans, unions supported equal pay for women.

In November 1942, the National War Labor Board issued General Order No. 16, permitting employers to “equalize the wage or salary rates paid to females with rates paid to males for comparable quality and quantity of work.” Many industries ignored the recommendation. Women protested that “comparable” was difficult to determine and that the same pay for the same job was a fairer standard. The Labor Board conceded that “there is no proof, scientific or otherwise,” that women were innately less capable than men, but no one in authority questioned sex- or race-based discrimination.

Millie Jeffrey of the United Auto Workers asked women on assembly lines what they needed. Responses included staggered shifts, on-site childcare, cafeterias with hot meals and take-out service, extended hours at banks, asking butchers to reserve meat for war workers and having grocers fill pickup orders. Without such services, absenteeism soared, earning women a reputation for unreliability. In all, 36% of American women worked during the war, compared to 70% of British women, who benefited from better support systems.

A decade after the government had dismissed married women workers, it now urged them to work. Employing white married women with children challenged social norms. In 1943 Congress amended the Lanham Act to provide $20 million to establish the country’s first and only universal childcare program. With matching funds, states established 3,102 centers. Mothers employed in war work paid fifty cents a day. Due to inconvenient hours and locations and maternal reluctance to leave children with strangers, the centers were under enrolled. Instead, women relied on relatives and neighbors. Older children cared for younger siblings or fended for themselves. In 1942, CBS Radio described them as “latchkey” children.

By 1945, 25% of married women and 12% of women with children under ten were working. While the Depression delayed marriage, the war accelerated it. Early in the war, married men got draft deferments. The birthrate jumped by 5%, from 19.4 births per thousand in 1940 to 24.5 in 1943, the highest rate since 1927. During the war every family dealt with housing shortages and rationing food, gas and tires.

At the end of the war, women, previously considered comrades-in-arms, became unseemly competition. Without war contracts, the aircraft and shipbuilding industries, which had employed the most women, dramatically cut their workforces. A Boeing supervisor declared that women “had done a grand job” but were glad to “go back to their homes and beauty parlors.” Experts warned that veterans expected to be breadwinners and that children would become delinquents without mothers at home. A government pamphlet cautioned that “the war . . . has given women new status, new recognition . . . Yet it is essential that women avoid arrogance and retain their femininity.”

Motivated by patriotism and paychecks, women had also enjoyed the camaraderie and independence their jobs provided. Many were reluctant to resume their former roles: 79% said they liked working. Women who continued to work found fewer opportunities and lower wages. Their participation in the work force fell from 36% in 1944 to 27% in 1947. Since then, according to the Labor Department, that number steadily increased.

In 2000, Congress authorized the Rosie the Riveter/WWII Home Front National Historic Park in Richmond, California, one of four shipyards on San Francisco Bay where Rosies built 450 Liberty ships. In addition to shipyard #3, the site included the SS Red Oak, a Ford truck and tank factory, a field hospital and childcare center. Credit goes to Irma Anderson, the first Black woman to serve on the Richmond City Council before becoming mayor. She had been the second Black woman to graduate with a nursing degree from Cornell. Anderson contacted the National Park Service. Judy Hart, who had led the Women’s Rights National Historic Park in Seneca Falls, became the founding superintendent of the Richmond site. It demonstrates the role of women and the diversity of the wartime work force. The Park gave Rosies their own home front.

Judy Hart, founding superintendent of the NPS’s first two parks recognizing women

Mae Krier, a seventeen-year-old Rosie who worked building bombers for Boeing in Seattle, lobbied for a National Rosie the Riveter Day, because “the men came home to parades [while] the women [got] a pick slip.” The day is not a national holiday; it depends on annual Congressional resolutions. In 2019, the Department of Defense recognized Krier’s efforts and fixed the date on March 21, her birthday.

Mae Krier at the World War II Memorial in 2024.

In 2020, a bipartisan bill sponsored by Senators Susan Collins (R-ME) and Bob Casey (D-PA) authorized awarding a Congressional Gold Medal to the remaining Rosies. It was presented in 2024 in the Capitol Visitor Center to two dozen Rosies in their nineties, many wearing red polka dots. Honorees included Marian Souza and Krier, both 98, Gloria McCormack, 99, and Velma Long, 106. Souza recalled, “I didn’t actually do anything . . . great, but I participated in something that was great.”

Rosies flexing at the Congressional Medal ceremony, April 2024

In January 2023, President Biden signed an Omnibus Appropriations Bill that included funding for a monument honoring Rosies on the National Mall. The National Memorial to the Women Who Worked on the Home Front passed the House almost unanimously; only Rep. Thomas Massie (R-KY) voted no. It passed the Senate with bipartisan support.

The proposal for a memorial began as a fifth-grade assignment: to build a model for a monument in Washington, for someone who hadn’t been honored. Raya Kenney, then 10, loved “A League of Their Own” and wondered what else women had done during WWII. Her curiosity led her to Rosie and the National Mall.

There are only two statues of real women among forty-four memorials on the Mall, of Eleanor Roosevelt at the FDR Memorial and of Vietnam nurses. The only relevant references Kenney could find were a bas relief (seen in Krier photograph above) and an inscription on the World War II Memorial. It quoted Oveta Culp Hobby, director of the Women’s Army Corps and the second woman to serve in the Cabinet, appointed by President Eisenhower as Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare. “Women who stepped up were measured as citizens of the nation, not as women . . .”

Kenney’s model was V-shaped, with black pillars to depict jobs women undertook during the war, as butchers, codebreakers, engineers, farmers, machinists, pilots, police officers, streetcar conductors, welders. She got an A and eventually established a foundation, found legislative sponsors and donors and sought site and design approvals. When the bill was signed, she was a twenty-year-old sophomore at Kenyon College. There is no guarantee the monument will be built.

Raya Kenney in 2014, age ten, and in 2024, age twenty

With or without a monument, Rosie the Riveter reminds us that “We Can Do It!” She embodies the strength and tenacity of American women.

The author at Hathaway Brown School in Ohio, during Women’s History Month, 2024.

SOURCES:

Photo credits: Public domain: National Archives, Library of Congress, National Park Service, Department of Defense, unless noted.

“Rosie the Riveter Day,” (January 4, 2024), https://veteran.com/rosie-the-riveter-day/

Nancy Baker Wise and Christy Wise, A Mouthful of Rivets: Women at Work in World War II (Jossey-Boss, 1994).

Donna B. Knaff, Beyond Rosie the Riveter: Women of World War II in American Popular Graphic Art (University Press of Kansas, 2012).

Sandy Fitzgerald, “Marilyn Monroe Was a Real-Life Rosie the Riveter in World War II,” Newsmax (June 5, 2014), https://www.newsm,ax.com/us/marilyn-monroe-rosie-the-riveter/2014/06/05/id/575399/.

Erin McDowell, “Who Was the Real Rosie the Riveter? Meet Naomi Parker Fraley,” Business Insider (March 8, 2025), https://www.businessinsider.com/author/erin-mcdowell

Sarah Pruitt, “Uncovering the Secret Identity of Rosie the Riveter” (September 19, 2023), https://www.history.com/news/rosie-the-riveter-inspiration

Gillian Brockwell, “Will the ‘Real’ Rosie the Riveter Please Flex?” Washington Post (March 20, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/history/2023/03/20/real-rosie-riveter/

“Child Care: The Federal Role During World War II,” CRS Report to Congress, www.congressionalresearch.com/RD20615/document.php

Rhaina Cohen, “Who Took Care of Rosie the Riveter’s Kids,” The Atlantic (November 18, 2015), https://www.theatlantic.com/business/archive/2015/11/daycare-world-war-rosie-riveter/415650/

Interview with Judy Hart, founding superintendent of Rosie the Riveter Park and author of A National Park for Women’s Rights (Cornell University Press, 2023).

Jordan Parker, “Irma Anderson: Former Trailblazing Richmond Mayor Dies at 93,” The San Francisco Chronicle (January 30, 2024), https://www.sfchronicle.com/bayarea/article/former-trailblazing-richmond-mayor-dies-18636310.php

Kayla Guo, “World War II’s Rosies, Heroes on the Home Front, Get Their Gold Medal,” New York Times (April 12, 2024), https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/01/16/raya-kenney-women-memorial-dc/

Petula Dvorak, “Her 5th-Grade Idea Was a Monument to Women. It Just Became Law,” Washington Post (January 16, 2023), https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/01/16/raya-kenney-women-memorial-dc/

“Raya Kenney’s Introduction to the Women of World War II,” https://wwiiwomenmemorial.org/history-of-the-monument

Elisabeth Griffith, FORMIDABLE: American Women and the Fight for Equality, 1920-2020 (Pegasus, 2022).

Thank-you for a really stirring article on the women workers of WW 2 - and their after history. I’ve sent it on to the women in our family with fond memories. Alf Cooley

So good what you are doing! I've learned so much I didn't know! Thank you, Emily Blair Stribling