MAY 17, 1954: BROWN & CONSTANCE BAKER MOTLEY

Note: Parts of this PINK appeared a year ago, on the seventieth anniversary of the Brown decision. This essay focuses more on the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court.

On a Monday in May 1954, the Supreme Court announced its seismic decision, Brown v. Board of Education, declaring racial segregation in public schools unconstitutional, because it violated the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. The unanimous decision overturned Plessy v. Ferguson (1896). It established the doctrine of “separate but equal” racial segregation and gave constitutional cover to white supremacy and Jim Crow apartheid.

The majority in Plessy held that the Fourteenth Amendment “could not have been intended to . . . enforce social, as distinguished from political, equality, or a commingling of the two races upon terms unsatisfactory to either.” The only dissenting vote was cast but John Marshall Harlan, who had been born into an enslaving family in Kentucky. “The Great Dissenter” declared: “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” That statement became a “Bible verse” to civil rights lawyers in the next century.

Brown put its actors into the headlines and into history: Chief Justice Earl Warren, attorneys Thurgood Marshall and Constance Baker Motley, and plaintiffs Linda Brown and Barbara Rose Johns, among others. President Biden’s appointment of Ketanji Brown-Jackson to the Supreme Court in 2022 renewed attention to Motley, whom President Johnson named the first Black female federal judge in 1967. Had President Carter had the opportunity to appoint a Supreme Court justice, experts speculated it might have been Motley.

Brown et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas was named for Oliver Brown. His family lived seven blocks from a white elementary school, but his eight-year-old daughter Linda had to travel twenty-one blocks to attend the Black school. When the principal of the white school refused to admit the third-grader, Rev. Brown sued.

By 1951, the Supreme Court had five school desegregation cases on its docket, from Delaware, Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Washington, DC, which it combined into Brown. It was not first alphabetically or chronologically, but it allowed the Court to emphasize that segregation was a national issue. Seventeen states enforced segregation and four allowed it, almost half the country.

The first school desegregation case submitted to a federal court in the twentieth century originated in Clarendon County, SC, “a place where life for Negroes had changed the least since slavery,” in a state whose 1895 constitution mandated racial separation. It was two-thirds African American. Black children walked nine miles to a one-room, board-and-tarpaper schoolhouse without plumbing. Their parents asked for a bus. Thirty busses were available to white students.

Rather than one bus, Thurgood Marshall of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund sought “equal everything.” When Briggs v. Elliott (1949) lost in federal district court in Charleston, Marshall appealed to the Supreme Court. (R.W. Elliott was the school board president.) Harry Briggs, a gas station attendant, and his wife, a maid, were the first of 107 parents and children who signed the petition. When the list was published, both were fired. Other repercussions followed. In January 2024, Harry Briggs’s son filed a petition asking the Supreme Court to rename Brown to Briggs.

As plaintiffs, girls outnumbered boys two-to-one. One suit was initiated by a student. Barbara Rose Johns, sixteen, led 450 students out of a shabby, segregated high school in Farmville, Virginia. Most Black schools ended in eighth grade, but Prince Edward County was considered relatively progressive. In 1938, to house 180 students, the Colored Women’s Club raised the money to build the Robert Moton High School, named for the second president of Tuskegee. By 1951, to accommodate overcrowding, tarpaper classrooms were added. Frustrated by their circumstances, students organized.

Barbara Johns’ two-week walkout was the first public protest in the postwar civil rights era. The Virginia NAACP agreed to take the case if she would sue for integration rather than equal facilities. The resulting case, Dorothy E. Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, Virginia, was incorporated into Brown. (Davis was the first name on the petition.)

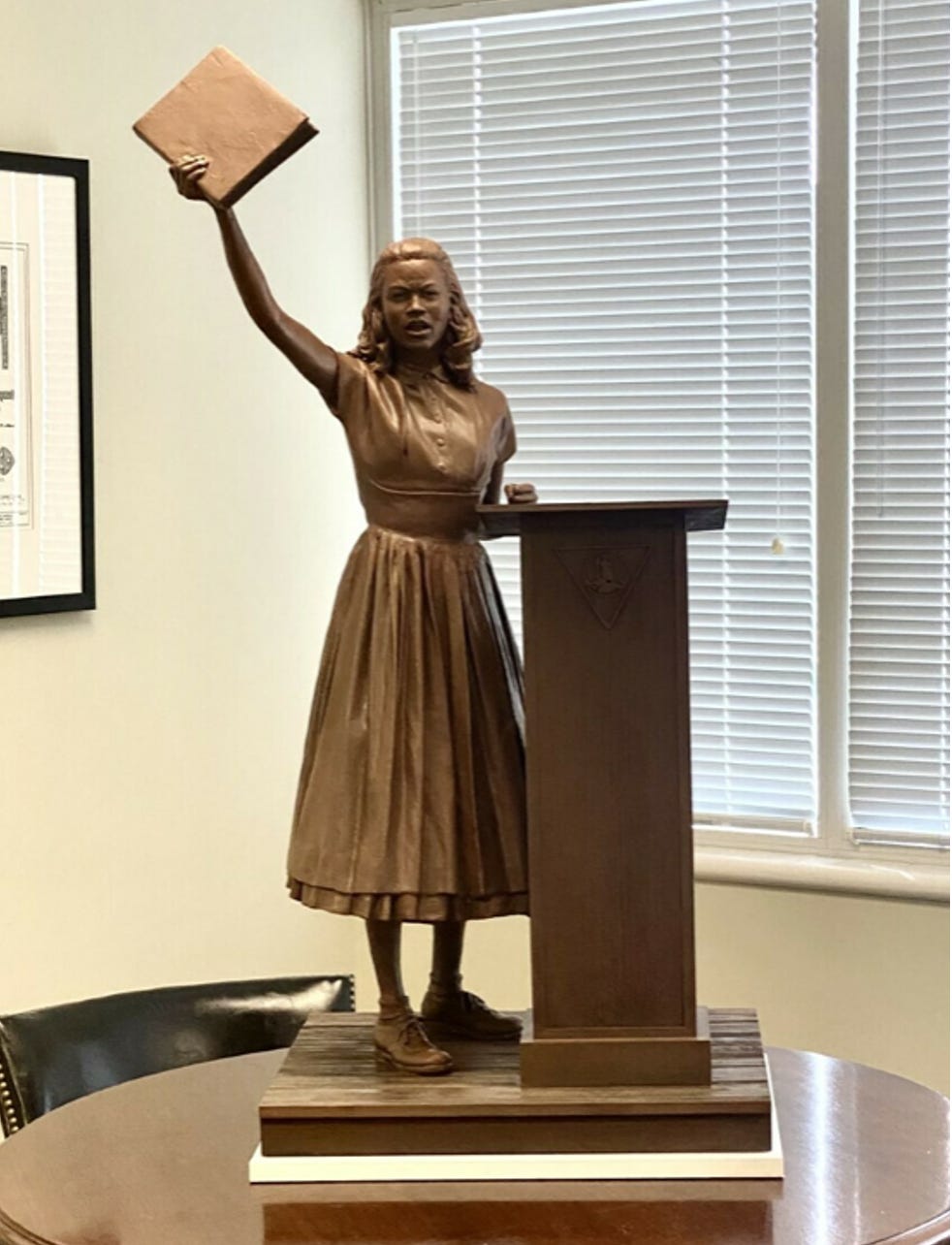

Feeling endangered, Johns finished high school with relatives in Alabama, attended Spelman College, graduated from Drexel University and worked as a librarian in Philadelphia. Rather than integrate, Prince Edward County closed all public schools from 1959-1964. It provided vouchers for white students to attend segregated academies and became a bastion of white resistance. In 2008, the Farmville library was renamed for Johns. In 2020, the Virginia legislature voted to replace the statue of Robert E. Lee in Statuary Hall in the US Capitol with one of Johns.

Model of Johns’ statue by Steven Weitzman (Virginia Dept. of Historic Resources)

The NAACP began challenging Plessy in the 1930s, at the direction of its legal counsel, Charles Hamilton Houston. The only Black student at Amherst, he graduated Phi Beta Kappa and first in his class in 1915. Fighting in France, Houston’s experience as an officer in a segregated Army battalion motivated him to pursue the law. “The hate and scorn showered on us Negro officers by our fellow Americans convinced me that . . . I would study law and use my time fighting for men who could not strike back.”

Houston enrolled in Harvard law school, was the first Black student elected to the law review, and graduated summa cum laude. After joining his father’s firm, he served as dean of Howard University law school, where he mentored Thurgood Marshall. Houston developed the “incremental strategy” that would culminate in Brown.

Under Houston and then Marshall, the LDF challenged teacher salary differentials, convictions based on coerced confessions, real estate covenants, exclusion of Black voters from primary elections and jury pools, and segregated schools and interstate travel. Its push to incorporate Black recruits into pilot training produced the Tuskegee Airmen.

Marshall was born in Baltimore in 1908. His mother was a teacher, his father a Pullman waiter and a steward at the exclusive Gibson Island Club. Marshall’s enslaved great-grandfather was freed before the Civil War. His son enlisted in the Union Army as Private Thoroughgood Marshall, which his impatient namesake shortened to Thurgood.

When he broke rules in high school, Marshall was required to read the Constitution. A star debater, he graduated from Lincoln University, an HBCU, but was refused admission to the segregated University of Maryland law school. His mother sold her wedding ring to help pay the tuition at Howard. Unable to afford boarding, he commuted, graduating first in his class in 1933, and joined the NAACP legal team. His first major case, Murray v. Pearson (1936) ordered the University of Maryland law school to integrate.

Marshall argued thirty-two cases before the Supreme Court, fourteen for the LDF, eighteen as US Solicitor General. He won twenty-nine. In 1961, President Kennedy appointed him to the US Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit in New York, which did not require Senate confirmation. President Johnson named him Solicitor in 1965, arm-twisting Southern senators to confirm him, before appointing him to the Supreme Court in 1967. Marshall served twenty-four years. Possibly the most significant jurist in American history, Marshall retired in 1991. When he died in 1993, the University of Maryland renamed its law library in his honor.

Justice Thurgood Marshall, 1976 (Library of Congress)

At the LDF, Marshall resisted defending or hiring women. He believed female plaintiffs were vulnerable to attacks on their character. Already known for his extramarital affairs, he wanted to avoid any whiff of impropriety at the LDF. The exception was Constance Baker Motley.

Born in 1921, Constance Baker was the ninth of twelve children. Her parents were from Nevis, the Caribbean island that was the center of the British Empire’s sugar trade until slavery was abolished in 1834. Her parents had mixed-race ancestors, British accents and educations, and the $25 passage price to immigrate. They settled in New Haven. Her father worked as a chef at Yale’s secret society, Skull and Bones, and owned his own home, but they were always poor, relying on leftovers from the college. Insisting their background was European, her father felt superior to African Americans.

“Connie” rarely experienced overt discrimination. She was not allowed on a public beach but she lived in a mixed neighborhood and graduated with honors from an integrated high school in 1939. Unable to afford college or find a job, she enrolled with the New Deal’s National Youth Administration. It provided jobs for people aged sixteen to twenty-five. For two years, she had random menial jobs, including as a seamstress and a furniture refinisher. She refused to become a hairdresser or follow her sisters into domestic service. Depressed by the prospect of lifetime drudgery, Baker immersed herself in community activism, becoming president of the New Haven Negro Youth Council.

In that role, she attended a meeting with the white board of a community center built for “the colored citizens of New Haven.” Its chairman, Clarence Blakeslee, Yale alumnus, industrialist and philanthropist, asked why few people used the facility? Baker responded that the community was not invested because they had no role in its leadership or programming. Impressed, Blakeslee offered to underwrite her education, “as far as she wanted to go.” Baker described his intervention as “a fairy tale.”

Young Constance Baker

In 1940, most Americans had not graduated from high school; only 6% of men and 4% of women earned college degrees. Few were Black students. In 1941, Baker enrolled at Fisk, the “Negro Harvard.” She wanted to experience “majority-black culture.” What she found in Nashville was Jim Crow racism. Humiliated by having to move into a rusty, segregated train car to travel south from Cincinnati, she transferred to NYU, earned a degree in economics, and enrolled in Columbia law school. In 1946, Baker became its second Black female graduate. Blakeslee attended the ceremony. Enduring racism, sexism and condescension, Baker claimed only to have “survived” law school.

Unable to secure a position in a white law firm, Baker pursued a clerkship at the LDF. Brainy and beautiful, Baker resisted Marshall’s sexist behavior, wholly inappropriate by today’s standards. She never accused Marshall of impropriety and was always grateful to the opportunities he provided. By aspiring to be an attorney, it was Baker who broke gender norms.

Motley & Marshall, undated (Courtesy of the Withers Family Trust)

She had also met Joel Motley, Jr., whom she married in August 1946. Quiet and unassuming, the opposite of her domineering father, her husband was supportive and successful, working as a real estate and insurance broker. The couple never revealed that the Illinois native had not attended college. They lived in Harlem and had a son in 1952. Like almost all Black women, she was a working mother.

The LDF employed four Black and two white overworked and underpaid lawyers. They shared cramped quarters. Motley researched cases challenging court marshals of Black veterans, restrictive real estate covenants, the exclusion of Black students from professional schools, and gerrymandered school district lines.

Her first courtroom appearance, in 1949, was on behalf of Black school teachers seeking equal pay in Jackson, Mississippi. Finding temporary housing and meals was difficult; grocery stores refused her service. The judge refused to call her Mrs. Motley, the case failed, and the plaintiff was fired. Motley returned to New York to demand equal pay from Marshall. She was the only female LDF attorney for fifteen years.

Preparing for the Brown case, six LDF lawyers, six secretaries and two clerks worked fifteen-hour days, including weekends, traveled 325,000 miles, and used twelve million sheets of mimeograph paper. Motley wrote the original complaint. Four men participated in the oral arguments. Marshall provided evidence from Black authorities: legal scholar Pauli Murray, historian John Hope Franklin, and psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark. Their famous doll test hypothesized that Black children chose to play with white dolls because learning in a segregated environment made them feel inferior.

When Brown reached the Supreme Court in 1952, only four justices were willing to overturn Plessy. The situation shifted when Chief Justice Fred Vinson died in September 1953. President Eisenhower appointed Earl Warren, three-term governor of California and Republican candidate for Vice President in 1948. Regretting his role in the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II, Warren supported the LDF appeal.

Warren’s vote made the decision 5-4, but in such a controversial case, he wanted unanimity. He delayed voting on Brown in conference until he had it. The final holdout was Stanley Reed of Kentucky, the last person to serve on the court without a law degree. Although he had written the majority opinion in Smith v. Allright (1944), banning all-white primaries, another Marshall victory, he resisted integration.

For all its consequence, Warren’s twelve-page decision was intentionally concise, comprehensive, and non-confrontational. “We conclude that, in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” When the Chief announced it, the New York Times printed a banner headline and ten pages of coverage.

Note photograph of Marshall and colleagues. (NYT Archives)

Brown failed to offer guidelines, a deadline, or consequences for noncompliance. While the NAACP pressed for immediate action, states stalled, claiming integration would be complicated and expensive. In May 1955, in another 9-0 decision, Brown v. Board of Education II outlined an implementation plan. The Court ordered defendants to “make a prompt and reasonable start” and advance “with all deliberate speed.” The oxymoron “deliberate speed” sabotaged progress. Brown was not fully enforced until passage of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, when less than two percent of Black students attended integrated schools.

Over twenty years as a trial and appellate lawyer, Motley handled hundreds of civil rights cases. She was the first Black woman to argue before the Supreme Court, winning nine of ten cases and assisting with sixty others. She made her court debut in 1961 in Hamilton v. Alabama, involving the right to counsel in a capital murder case.

Motley forced the integration of Clemson and the universities of Alabama, Florida, Georgia and Mississippi. She secured the admission of Charlene Hunter (now Hunter-Gault) and Hamilton Holmes to the University of Georgia in 1961 and notably escorted Air Force veteran James Meredith onto the University of Mississippi campus in 1962. She integrated restaurants Memphis and lunch counters in Birmingham. She represented the 1,100 children who had been fire-hosed and then expelled for participating in the Birmingham Children’s Crusade and bailed Dr. King out of jail. But when Marshall left the LDF in 1961, his successor was Jack Greenberg, his white co-counsel.

James Meredith & Constance Baker Motley, 1963 (NAACP-LDF)

In 1963, New York Democrats asked her to fill an unexpired term in the state senate. She agreed if she would continue with the LDF, becoming the first Black woman in that body. In 1964, she was elected to a full term. In February 1965 she was unanimously chosen by the Manhattan city council to fill a vacancy as borough president. With the endorsement of the Democratic, Republican and Liberal parties, she was elected to a full term.

New York Mayor Robert Wagner swears in Motley as Manhattan Borough President in 1965, shown with her son and husband.

In 1966, President Johnson nominated her to be US District Judge for the Second Circuit in New York. Mississippi Democrat James Eastland, who chaired the Senate Judiciary Committee, held up her confirmation for seven months. She was the first Black woman and third female appointed to the federal bench. Motley was named Chief Judge in 1982 and continued to try cases as Senior Judge after 1986.

In her thirty-plus years on the court, she decided landmark cases in civil rights and criminal law. She protected women in the workplace, for example insisting that female sports writers be allowed into the Yankees locker room. She demanded due process and humane treatment for welfare recipients, Medicare patients and the incarcerated. She mentored her younger colleague, Sonia Sotomayor, appointed in 1991. President Clinton awarded her the Presidential Citizens Medal and the NAACP gave her its highest award, the Springarn Medal, in 2003. She remained a judge until her death in 2005, at eighty-four.

Constance Baker Motley was a tall, handsome, regal woman with a captivating voice, a gracious manner, and an elegant wardrobe. A shrewd strategist, she was always dignified – and insisted in dignity and equal rights for all.

PHOTO CREDITS: Public domain unless noted.

SOURCES:

Richard Kluger, Simple justice: The History of Brown v. Board of Education and Black America’s Struggle for Equality (Vintage, 2004).

Briggs v. Elliott, https://www.nps.gov/brvb/learn/historyculture/socarolina.htm

Kathleen Parker, “S.C. Plaintiffs Seek to Correct the Civil Rights Record,” https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/2023/12/30/brown-v-board-education-supreme-court-thurgood-marshall-south-carolina-briggs/

Davis v. County School Board, https://www.nps.gov/brvb/learn/historyculture/virginia.htm

Virginia Department of Historic Resources, “Preliminary Model of Virginia’s Barbara Rose Johns Statue for US Capitol Approved” (August 7, 2023), https://www.dhr.virginia.gov/blog-posts/barbara-rose-johns-maquette-approved-for-us-capitol/

Linda Greenhouse, “Thurgood Marshall, Civil Rights Hero, Dies at 84,” NYT (January 25, 1993),

https://www.nytimes.com/1993/01/25/us/thurgood-marshall-civil-rights-hero-dies-at-84.html

Constance Baker Motley, Equal Justice Under Law: An Autobiography (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1998).

Gary L. Ford, Jr., Constance Baker Motley: One Woman’s Fight for Civil Rights and Equal Justice Under Law (University of Alabama Press, 2018).

Tomiko Brown-Nagin, Civil Rights Queen: Constance Baker Motley and the Struggle for Equality (Pantheon, 2022).

Douglas Martin, “Constance Baker Motley, Civil Rights Trailblazer, Dies at 84,” NYT (September 29, 2005, https://www.nytimes.com/2005/09/29/nyregion/constance-baker-motley-civil-rights-trailblazer-dies-at-84.html

Darlene Clark Hines et. al., eds., Black Women in United States History: From Colonial Times to the Present (Carlson Publishing, 1990).

Elisabeth Griffith, FORMIDABLE: American Women and the Fight for Equality, 1920-2020 (Pegasus, 2022).