Author’s Note: Because of all the Roosevelts named in this essay, I refer to my subject as “ER” or Eleanor, even before she became a one-name icon.

Eleanor Roosevelt’s biography is a story about transformation and an example of the power of persuasion and moral authority. No one who had known her as a child would have anticipated her future as First Lady, international icon and advocate for human rights. Born on October 11, 1884, Anna Eleanor Roosevelt was a year older than suffragist Alice Paul, but she did not identify as a feminist until the 1920s.

Her gorgeous mother disdained her looks. Her alcoholic father left her with doormen while he drank in private clubs. By the time she was ten, both were dead, leaving her an orphan in the care of her grandmother and private tutors. Her salvation was attending a girls’ boarding school in England at age fifteen. Allenwood’s insightful headmistress encouraged her “superior intellect” and leadership skills. In 1903, a confident, willowy young woman returned to New York. She taught calisthenics in a settlement house as a member of the Junior League, made her debut at the Waldorf and met the dashing Franklin Roosevelt, her fifth cousin. He found her the most interesting woman he had ever met.

Eleanor, 1898, age 14

At her 1905 wedding, the bride was overshadowed by her uncle, President Theodore Roosevelt, who gave her away. As a young wife, she was an overwhelmed mother, bearing six children in ten years. One died before his first birthday. She was intimidated by her mother-in-law. Sara Roosevelt occupied the townhouse next door and ordered connecting doors. Like many upper-class women, Eleanor’s status derived from her relationship with powerful men: her uncle the president and her husband, a rising politician who became Assistant Secretary of the Navy in the Wilson administration, as TR had been under McKinley.

1918: Anna, Franklin Jr, James, John and Elliott with their parents

In 1918, when she was thirty-three and her children ranged in age from two to twelve, Eleanor discovered that her husband was having an affair with her social secretary, Lucy Rutherford Mercer. Divorce was unacceptable to her husband and mother-in-law, but their traditional marriage ended. It would evolve into a unique political partnership as Eleanor acknowledged her own ambitions, priorities and passions.

In 1920, Franklin ran for vice president on the losing Democratic ticket. His political career was sidelined after he was stricken with polio in 1921, but Eleanor convinced him to remain engaged, inspiring his recovery and rehabilitation. Initially acting as his surrogate, the once shy society wife became an independent political player.

During the 1920s, she founded a furniture-making business and established her household at Val-Kill. It was located down the road from the Roosevelt family’s Hyde Park manor overlooking the Hudson River, where her husband and his mother claimed the chairs flanking the living room fireplace. In 1927, she and her Val-Kill partners purchased Todhunter, a girls’ school in New York City. Eleanor served as associate principal and taught American history, literature and current events until 1933.

She allied herself with Carrie Catt, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley and Alice Hamilton. She joined international peace organizations, the League of Women Voters, the Women’s Trade Union League and the Women’s City Club of New York City, a club house for activists like Frances Perkins and Molly Dewson. Eleanor invited Black educator Mary McLeod Bethune to her home for dinner, a first for both. These women became her political and friendship network.

“ER” volunteered with the women’s division of the state Democratic Party, registering and organizing women. She toured New York state in her blue roadster. She endorsed Sheppard-Towner and the Child Labor Amendment, but not the Equal Rights Amendment, because her allies opposed it. Eleanor won a party fight about who would choose delegates to the 1924 national convention, where she chaired the subcommittee on women’s issues. The Committee on Resolutions rebuffed her proposals. She recalled seeing “for the first time where women stood . . . outside the door of all important meetings.” Eleanor aspired to be an insider.

At the 1924 state Democratic Convention, Franklin Roosevelt, supported by his sons and iron leg braces, nominated Al Smith for his third term as governor. Eleanor joined Smith’s winning campaign against her cousin, Theodore Roosevelt, Jr. In 1926 she urged the Albany legislature to limit the work week to forty-eight hours. She was charged with disorderly conduct for picketing a box-making company to protest its working conditions.

In 1928, Franklin nominated Smith for president and ran to replace him as governor. Eleanor campaigned for Smith rather than her husband. Smith lost, FDR won and Eleanor moved to Albany. In 1932, Roosevelt was elected President. The new First Lady was reluctant to return to a city steeped in protocol, the scene of her husband’s affair.

1932, age 48

After a decade of independence, she resisted traditional expectations. Eleanor challenged assumptions about how political wives should behave. She dressed as she wished, drove herself and expressed her opinion. She became the voice of the under-represented: women, the rural poor, Jews and African Americans. When the Bonus Army of Great War veterans returned to Washington in 1933, she visited their campsites. “Hoover sent the Army,” one commented. “Roosevelt sent his wife.” It’s more likely she went on her own.

During the four-month transition, Eleanor published three books. In one, she reassured readers that the nation had survived earlier crises, thanks to women. Eleanor produced articles and books for the rest of her life. From 1935 to 1962 she wrote a daily column called “My Day,” syndicated in ninety newspapers; contributed a monthly column to Woman’s Home Companion; hosted a weekly radio show and spoke widely.

Annoyed that she depended on an allowance from her husband, she was determined to match his salary, earning $75,000 in 1933. The first employed First Lady, she ignored the critics, paid her secretary’s salary, underwrote pet projects and donated her remaining income to charity.

Both Roosevelts curried positive relationships with the press. The First Lady hosted 348 press conferences in twelve years. She invited only female journalists, forcing news outlets to hire women. When the Gridiron Club barred women reporters from its annual dinner, she hosted a Gridiron Widows dinner at the White House. She became so close to Lorena Hickok, who covered the campaign, that the reporter’s objectivity was questioned. “Hick” took a federal job and moved into the White House, where their private relationship continued. Sensitive to criticism about her appearance and children, she advised women in public “to develop skin as tough as a rhinoceros.”

ER used her White House role to advance women, beginning with government appointments. She and Molly Dewson, whom FDR had put in charge of the Women’s Division of the Democratic National Committee, compiled lists of qualified women. Fifty of the sixty women they proposed were appointed, including Frances Perkins as Secretary of Labor, the first female cabinet member.

With Frances Perkins

Eleanor and Dewson worked hard to attract women and African Americans to the Democratic Party. Black voters supported Hoover in 1932, unimpressed by FDR and loyal to the party of Lincoln. They despised Southern Democrats. In 1934, Democrats won two-thirds of both chambers but the Senate was still controlled by segregationists, whose votes FDR needed.

African Americans had one White House ally. Eleanor was undeterred by the ferocity of racist opposition to relief programs for Black Americans. Vocal in her support of civil rights, ER insisted that New Deal programs target 10% of welfare programs for African Americans, in proportion to their population, primarily through segregated initiatives. She invited notable Black men to the White House for an “unrestrained” discussion about lynching, inadequate jobs and the need for clean water and housing.

She arranged for Mary McLeod Bethune to serve with the National Youth Administration, making her the first Black federal administrator and soon the highest ranking. Bethune organized the forty-five African Americans working in sundry executive offices into the “Black Brain Trust.” In 1939 she arranged for Marian Anderson to sing at the Lincoln Memorial. Earlier that year Eleanor, “speaking for myself, as an individual,” publicly condemned lynching. Attending a segregated public meeting in Birmingham, Alabama, she refused to take sides and moved her chair into the center aisle. Sheriff Bull Connor objected.

With Mary McLeod Bethune

Her support for Black Americans became a campaign issue, used both for and against FDR. During the war, the First Lady flew with the Tuskegee “Red Tails,” to demonstrate her support for training Black pilots in the segregated armed services. After the war she served on the boards of the NAACP and CORE. As one Georgian sniped, “We didn’t like her one bit; she ruined every maid we ever had.”

Events in Europe forced Eleanor to address anti-Semitism, including her own. According to one biographer, she had the “impersonal and casual . . . [biases] of her generation, class and culture.” She opposed bigotry but was oblivious to demeaning stereotypes. She did not socialize with Jewish allies and had few Jewish friends. Eleanor hosted fundraisers to support Jewish refugee children and battled the “striped pants bigotry” of the State Department, but FDR did not create the War Refugee Board until 1944. Indifference and inaction condemned countless Jews to the Holocaust.

President Roosevelt died on April 12, 1945, in Warm Springs, Georgia, in the company of Lucy Mercer. In Washington, Mrs. Roosevelt informed her children and the Vice President. Truman respected smart women and began a “robust correspondence” with the former First Lady. In November 1945 he appointed the country’s longest-serving First Lady to the first US delegation to the United Nations, meeting in London. He had earlier sent Mary McLeod Bethune to San Francisco, where she was the only woman of color in the world to have official status at the founding of the United Nations.

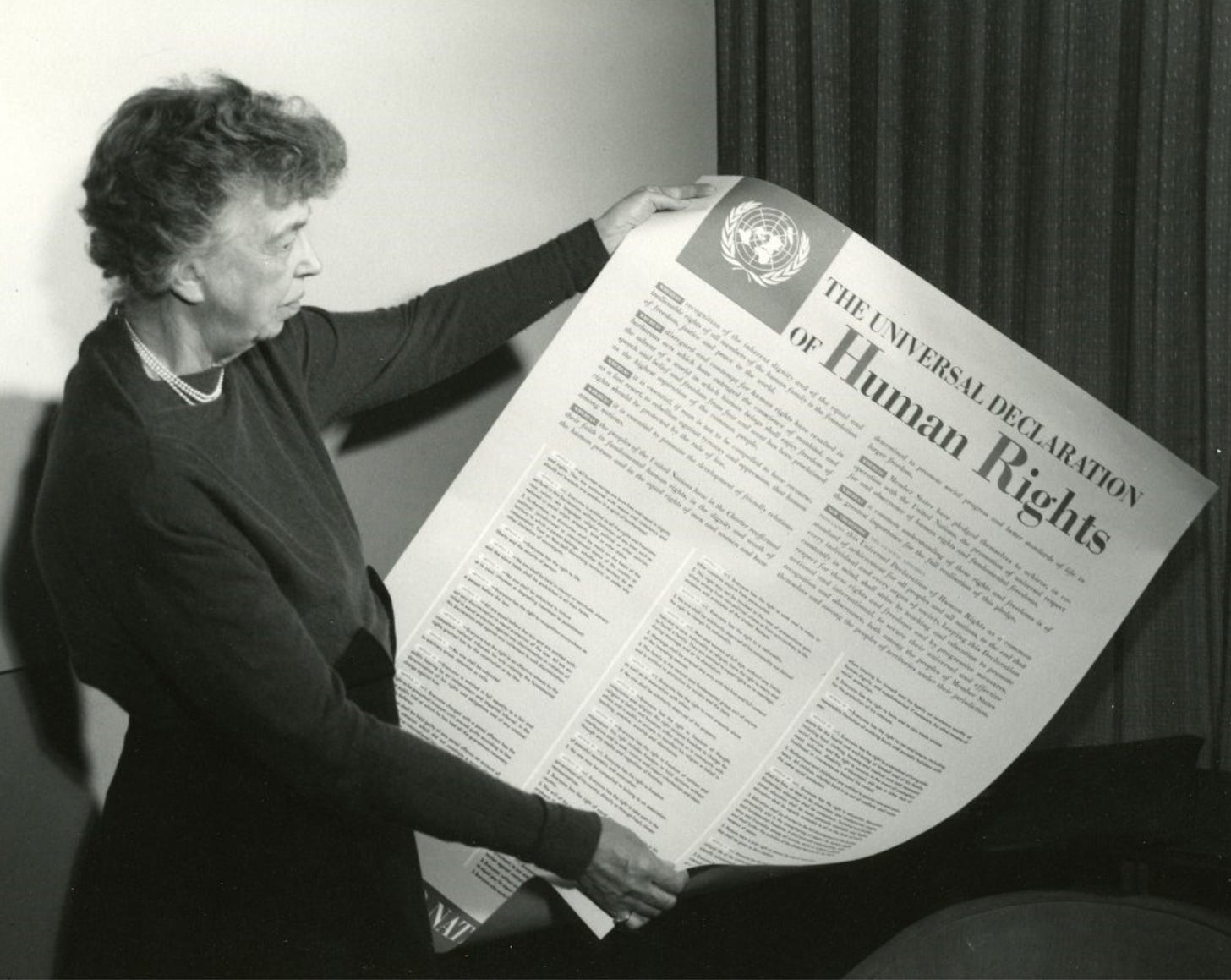

In London, Eleanor used what journalists ridiculed as her “shrill . . . strident and schoolmarmish” voice to promote human rights. She was unanimously elected to chair the committee that established the UN Human Rights Commission. It drafted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, issued in 1948. The Declaration delineated thirty fundamental political, economic, social and cultural rights to which everyone was entitled. “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights . . . without distinction . . . such as race, color, sex, language, religion, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.”

The Declaration lacked an enforcement mechanism and was not included in the binding international treaty signed by member nations. Eleanor resigned in 1953, to allow President Eisenhower to appoint a Republican. Already “First Lady of the World,” she remained active globally and domestically. She attacked the Un-American Activities Committee and campaigned for Democrats.

Eleanor’s international perspective did not change her position on the Equal Rights Amendment, which she continued to oppose, although less publicly. Alice Paul, the amendment’s autocratic author, had alienated Democrats, unions and social justice activists by relying on Republican support and undermining protective legislation for working women. Paul’s opponents were Eleanor’s allies.

After 1936, when FDR lost the House, Republican subcommittees held hearings on the ERA. After the Supreme Court upheld the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act, safeguarding protective legislation was less pressing. In 1940, the Republican platform supported “submitting” the ERA. World War II revived interest in the amendment and increased bipartisan support, but ER, Perkins and Catt remained adamantly anti. In 1943, New Deal appointees testified that the ERA was “impractical, dangerous, abstract, vague and legally unsound.” Democrats added equivocating ERA language acceptable to labor to its 1944 platform.

Truman dismissed the ERA as “a lot of hooey,” but the Senate held its first floor vote in 1946. It failed and would continue to lose during the 1950s, gutted by the Hayden amendment. House Judiciary chairman Emanuel Celler (D-NY) refused to release it from his committee. The ERA was opposed by progressives, organized labor, Catholics, Southerners and many women.

Eleanor kept a low profile on the ERA. After the 1960 election, when women were less predictably Democratic voters, Kennedy’s highest ranking female appointee, Esther Peterson, Director of the Women’s Bureau, proposed a President’s Commission on the Status of Women. It was designed to counter support for the ERA. Publicly, “The President’s Commission was established to examine the needs and rights of American women today and to make recommendations for the elimination of barriers that result in waste, injustice and frustration.”

President Kennedy established the PCSW by Executive Order in December 1961. He persuaded Mrs. Roosevelt, the best-known woman in America, to chair the Commission, despite her disdain for Joe Kennedy and support for Adlai Stevenson. She had already met with the President, in March 1961, to press for more appointments for women. Only nine of 240 positions requiring Senate confirmation had gone to women. She was a feisty seventy-seven.

ER, JFK & Esther Peterson

Peterson, as vice chair, vetted the twenty-six commissioners, a group “not so diverse that it would be hopelessly divided.” There were fifteen women and eleven men: four cabinet secretaries; two senators and two representatives; one Jew, Catholic and Protestant; two members of organized labor; one homemaker and no one from the National Woman’s Party. Dorothy Height, head of the National Council of Negro Women, was the only Black member. For credibility, Peterson appointed one ERA supporter, Texan Marguerite Rawalt, the first female president of the Federal Bar Association. She was the former head of the Business and Professional Women, long allied with the NWP.

Peterson also selected the executive director, from the AFL-CIO, and approved the staff and public members of seven committees. These included Pauli Murray, Mrs. Roosevelt’s protégé since the 1930s. In the 1960s, Murray was the first Black candidate for a doctorate in the science of the law, Yale’s most advanced degree. According to Alice Paul, the PCSW was “loaded . . . against equality.” Murray called it the “first high-level consciousness-raising group.” The attorney noted parallels between racism and sexism and argued that the equal protection clause should be sufficient, if the courts would apply it.

The Commission agreed, concluding: “The Commission believes that this principle of equality is embodied in the 5th and 14th amendments of the Constitution . . . [so a] constitutional amendment need not now [italics added] be sought in order to establish [it].” Rawalt insisted on inserting “now” as a workable compromise. “What they term a compromise,” raged the NWP, “is really what [UAW leader Walter] Reuther and Peterson wanted.” The Commission unanimously recommended improving women’s access to education, childcare and equal and part-time employment. It reassured the public that “widening the choices for women beyond their doorstep does not imply neglect of their . . . responsibilities in the home.”

Eleanor Roosevelt redefined the role of First Lady and defined liberalism. With actual power, she used her position to influence policy. Her endorsement of international human rights challenged the white supremacy of developed nations. When Mrs. Roosevelt died in November 1962, President Kennedy left her seat vacant: “It is my judgment that there can be no adequate replacement.”

The President’s Commission on the Status of Women presented its sixty-page report, American Women, on October 11, 1963, the seventy-ninth anniversary of Eleanor Roosevelt’s birth.

“Eleanor Roosevelt” (1949) by Douglas Chandor, White House Collection

SOURCES:

Photo credits: public domain: National Archives, Smithsonian National Portrait Gallery

https://www.fdrlibrary.org/er-biography

Allida M. Black, Casting Her Own Shadow: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Shaping of Post-War Liberalism (Columbia University Press, 1997).

Doris Kearns Goodwin, No Ordinary Time: Franklin and Eleanor Roosevelt (Simon & Schuster, 1995).

Blanche Wiesen Cook, Eleanor Roosevelt, three volumes (Viking, 1992, 1999, 1992).

David Michaelis, Eleanor (Simon & Schuster, 2020).

Eleanor Roosevelt, “Interview with President John F. Kennedy” (April 18, 1962), https://youtube/XdfVxB-sXxc?si=XWHgFHUrHNyIo257

Elisabeth Griffith, FORMIDABLE: American Women and the Fight for Equality, 1920-2020 (Pegasus, 2022).

“The Legacy of JFK’s Commission on the Status of Women,” C-SPAN 3 (October 4, 2013), https://www.c-span.org/video/?315133-2/presidential-commission-status-women.