Images of the Depression in our common memory include breadlines, tar-paper shacks, sharecroppers, hobos and migrant mothers. Only rarely do they include the goddesses of the silver screen, wearing slinky satin evening gowns, sipping martinis and smoking cigarettes -- Jean Harlow, Claudette Colbert, Katharine Hepburn, Carol Lombard. Their curve-clinging dresses were made possible by the invention of the tampon.

To deal with monthly menstrual cycles, most American women relied on rags, sheepskin, cheesecloth sacks stuffed with cotton, pieces of fabric pinned to underpants, or straw. Being “on the rag” was a euphemism for having one’s period. Among the first reforms sought by women working in factories were restrooms, so they would have privacy to change their menstrual dressings, which were hidden under skirts. It would have been a challenge to be clean or comfortable.

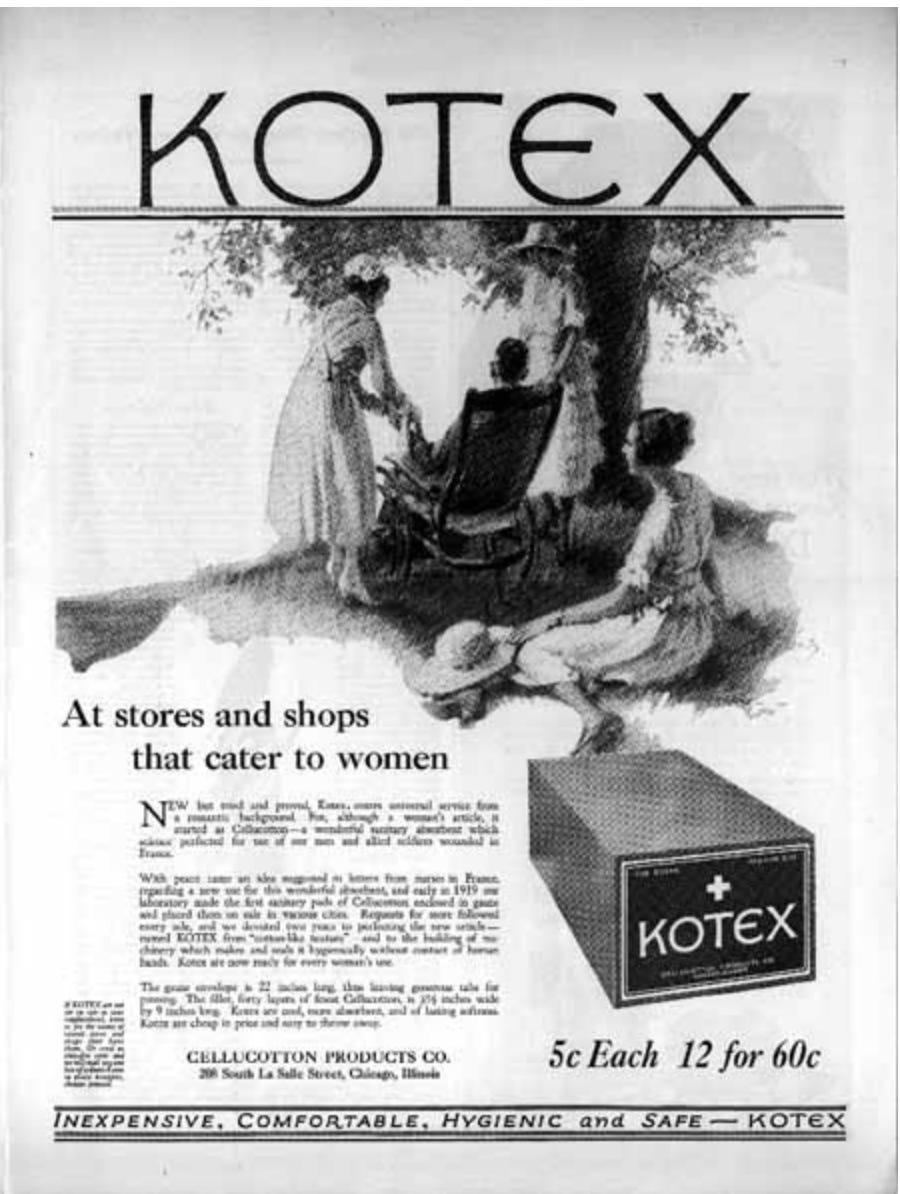

The Great War produced a surplus of high-absorption, cellulose-bandages. Made of wood pulp fiber, they were better than cotton for absorbing blood. In 1921 Kimberly-Clark mass-produced the first sanitary pads, called “Kotex” for its cotton-like texture. They were held in place by a belt.

Dr. Earle Cleveland Haas, a Colorado-based osteopath, general practitioner and entrepreneur, invented a flexible ring for a contraceptive diaphragm. He sold the patent for $50,000. In 1931, he designed a device to replace rags or belts. Haas got the idea from women who inserted vaginal sponges as contraceptives or to absorb menstrual flow. Egyptian, Greek and Roman women had used fiber-wrapped inserts. His innovation was the telescoping cardboard tube, so women would not have to touch the cotton insert.

His application for a patent for a “catamenial device” was granted on September 12, 1933, as US Patent No. 1,926,900. Catamenial, Greek for “monthly,” described menstrual cycles. The word tampon came from the medieval French word tampion, a cloth stopper.

When neither Kimberly-Clark nor Johnson & Johnson was interested in his invention, Haas sold the patent to an immigrant Denver businesswoman, Grace Tendrich, for $32,000. Initially she made them on her sewing machine. In 1936 she founded the Tampax company, served as its president and hired female staff to produce and market the first commercial tampons.

Because is was related to sex, menstruation was a taboo topic. Religious leaders called tampons immoral, claiming they destroyed physical evidence of virginity and encouraged masturbation. They are banned today in much of Asia and several Muslim countries. Tendrich countered with an advertising campaign heralding a “new day for womanhood.” She hired female athletes to be brand ambassadors and published educational materials.

Thousands of women mobbed the Tampax display in the Hall of Pharmacy at the 1939 World’s Fair, where a registered nurse answered questions. Competition from a “menstrual cup,” another ancient solution, was curtailed by rubber shortages during World War II. Kotex remained the most popular product until the war, when women entering the military or the workforce donned trousers.

In 1945, the Journal of the American Medical Association approved tampons for teenagers, asserting, “The tampon has a caliber [width] that does not impede standard anatomic virginity.” The expert also claimed that tampons were less “stimulating” than pads. Medical authorities believed that prudish attitudes about sexual organs led to ignorance, untreated disease and sexual issues in later life. This was the era that would produce the Kinsey Reports (1948), Masters & Johnson (1957) and the Pill (1960).

Magazines carried ads for menstrual products, but they were banned on television in the US until 1972. By then the message had shifted from modesty and daintiness to the physical freedom to be active every day of the month. In 1985, a decade before the Friends franchise, a pre-Monica Courtney Cox made a commercial for Tampax: “[They] can change the way you feel about your period.” It was the first time the word period was used in broadcast advertising.

Proctor & Gambal bought Tampax in 1997. The multi-national consumer goods giant touts Tendrich as an early “girl boss.” P&G sells Tampax products in seventy countries, a 30% global market share. Johnson & Johnson, its nearest rival, has less than a 20% share. Yet the use of tampons has steadily declined, due to “period cessation” caused primarily by oral contraceptives and to competition from products seen as more ethical, ecological and sustainable. One new brand’s tag line is “bleed red, think green.”

In recent years, local governments have addressed the issue of “menstrual equity” and “period poverty,” the lack of menstrual products in high poverty areas, shelters, Indigenous communities and correctional facilities. Tampons and pads, like diapers, are expensive. More than half the states and Washington, DC, have approved laws funding and increasing access to menstrual products in public schools. Recently access became an issue in the presidential campaign.

On July 1,2024, a law signed by Minnesota Governor Tim Walz went into effect, requiring public schools to provide free menstrual products “to all students who needed them,” beginning in the fourth grade. The bill was spearheaded by two middle school girls. Former President Trump labeled the governor “Tampon Tim” and accused him of placing pads and tampons in boys’ restrooms for transgender students, linking that to the governor’s support for LGBTQ rights.

The bill’s legislative authors intended to include trans students and to put products wherever they were needed, in girls’ restrooms, gender-neutral restrooms and nurses’ offices. Individual school districts are responsible for meeting the requirements. Most principals chose not to put products in boys’ rooms, given their adolescent lack of maturity. As Maarit Mattson, fifteen, one of the students who helped initiate the legislation, declared: “It isn’t part of a political agenda. [It’s] to make students feel safe.”

SOURCES:

Author’s note: I could find no obituary for Tendrich; nor is she included in Notable American Women, the first biographical dictionary of significant women.

Photo credits: public domain

Joan Jacobs Brumberg, The Body Project: An Intimate History of American Girls (Random House, 1997).

Emily Cochrane, “What Minnesota’s Law on Tampons in Public School Actually Does,” New York Times (August 17, 2024), https://www.nytimes.com/2024/08/16/us/politics/walz-free-tampons-schools-minnesota.html.

Sophie Elmhirst, “Tampon Wars: The Battle to Overthrow the Tampax Empire,” The Guardian (February 11, 2020), https://www.theguardian.com/society/2020/feb/11/tampon-wars-the-battle-to-overthrow-the-tampax-empire.

Elissa Stein and Susan Kim, FLOW: The Cultural History of Menstruation (St. Martin’s Press, 2009).

Loved your post today about something I know almost nothing about. Thanks. RD